THE REALITY OF BEING BIRACIAL: BLACK AND SOUTH ASIAN/BLINDIAN

THE REALITY OF BEING BIRACIAL: BLACK AND SOUTH ASIAN/BLINDIAN

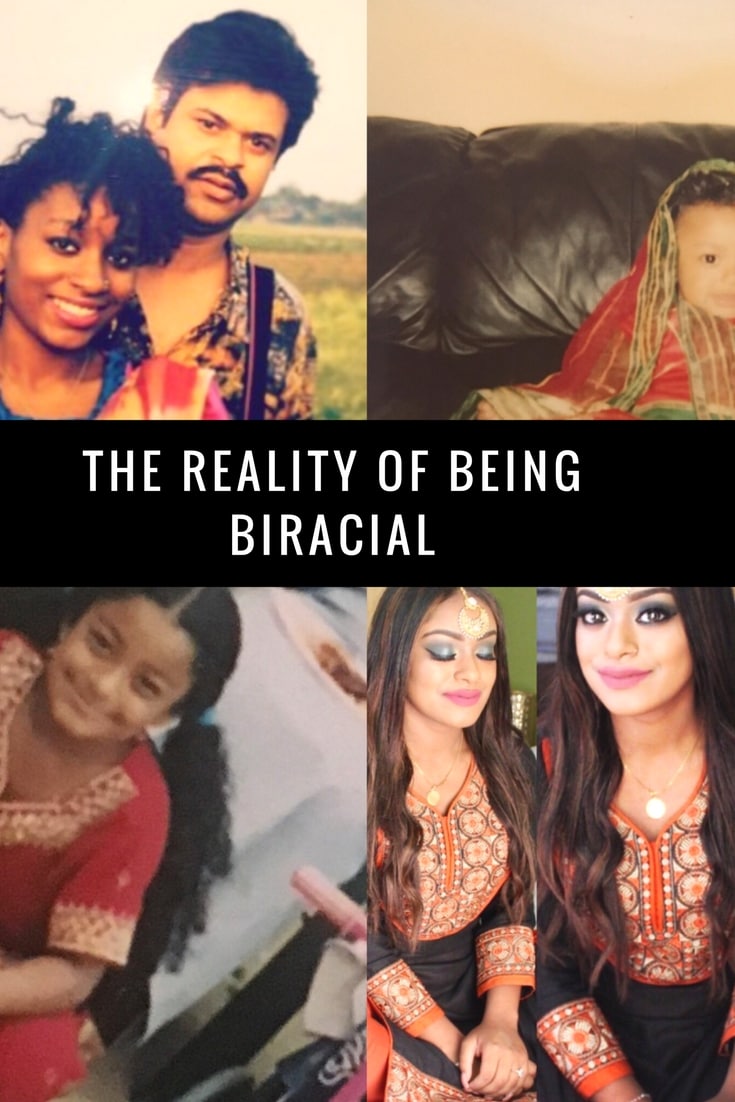

An Interview with Sitara Abbas

“One’s eyes serve as the windows to the world and one’s mind serves as the curtains to the windows. To be able to abdicate one’s biases and prejudices, emerging and embracing the beauty of what may not be akin, is to be open-minded.”

WHO AM I?

My name is Sitara Abbas. I come from a very diverse background; my mother is a descendent of the Black-Hawk Native Indians, who are recognized for their notorious methods of survival, courageous acts of defense, and their richness in the preservation of culture. Tracing back into her history are also black Americans, who were initially labeled as slaves, but worked hard, struggling hand in hand, towards achieving civil rights. My father immigrated from a small third-world country in southeast Asia known as Bangladesh, where he witnessed first-hand, the traumatic events of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. His ancestors, known as the Nawabs, were prosperous leaders of the Persian Mughal Empire of South Asia. Most individuals may think that’s intriguing. Sure, to be a part of such beautifully unique ethnic cultures is a blessing. However, such diversity facilitates alienation and micro-aggression: the unintended and indirect facilitation of racism. It creates a buffer between one’s self-identity and what one is identified as. Nonetheless, as the American scholar, Brené Brown eloquently stated, “Owning our story and loving ourselves through that process is the bravest thing that we’ll ever do.”

DISCOVERING I’M NEITHER ALL BLACK OR ALL INDIAN

Imagine an innocent child; she is approximately three feet in height; she has big curly ringlets forming a mane upon her head; she is dressed in traditional Pakistani ethnic clothing and she has henna on her hands. She is dressed up for Eid, a sacred Islamic holiday held in honor of the conclusion of Ramadan, a month of forgiveness, worship, and sacrifice. She walks into her first grade class where forty eyes are glued to her perceived eccentricity. Her classmates inquire what “the red stuff” on her hands is, why she is wearing ‘Indian clothing’, and wonder if she is even Indian to begin with. At such a young age, she doesn’t quite comprehend the inquisitiveness of her peers. However, everyone’s desire to know her background triggers her thirst for knowledge about her perceived uniqueness; it is a thirst waiting to be quenched. The overwhelming inquiries and subliminal micro-aggressions stimulate a vulnerability to isolation. From this moment forward, she realized that she was innately, irreconcilably, different.

TOO BLACK TO BE BANGLADESHI TOO BANGLADESHI TO BE BLACK

Envision a developing adolescent, not only embarrassed by her inevitable singularity, but also propelled by the pressures of self-identification and public acceptance. Disapproving South Asians of her community neglect her biracial status and display a strong racial preference, resulting in the instantaneous abandonment of her African-American culture. It is exhausting having to explain why, and how she is consisted of so many diverse cultures. Being ‘too black’ to be Bangladeshi and being ‘too Bangladeshi’ to be black catalyzes the desertion of her cultures and the negligence towards her traditions. She yearns to understand herself, understand her culture, and understand how to appreciate it. To be a part of two races that are too often degraded places her at the bottom of what she perceives as the modern social caste system. She remains on her quest, in pursuits of finding a place where she ‘belongs’, wishing that the world could be blinded to prejudices and enlightened with embracement.

THE DISAPPERANCE OF JUDGEMENT

Picture a maturing, young-adult stepping onto the foreign grounds of Bangladesh for the very first time. Hundreds of eyes gazing at her blended features cause her adrenaline to increase, and nerves to eat her alive. She climbs down from her rickshaw and walks up the endless stairs into her family’s home located in Old Dhaka, also formerly known as East Pakistan. Caught by surprise, she finds fifty smiling faces, one-hundred adoring eyes, and not a slight bit of judgment. She gives all of her family, whom she is meeting for the first time, her greetings. She acknowledges that unlike ever before in her lifetime, she is not being seen as, “The dark-skinned, half-black, half-Bangladeshi girl who speaks the language of Pakistan”, but as a beautiful human that is a part of a welcoming family. She comfortably speaks in her family’s native language: Urdu, exchanges laughter, smiles, hugs, and for the first time, feels like she belongs. In this very moment, she realizes the beauty of her dissimilarity and the value of open-mindedness.

SOCIETY’S PERCEPTION AND HOW I CELEBRATE BEING BIRACIAL

Until this day, I know that I am innately different, but I have learned that being different is not irreconcilable. Although still young, the battle I’ve fought with myself for over a decade in order to determine my own identity has built collective wisdom. It can be proven true that the power of diversity has the potential to build better societies. It is only those whom open their minds and hearts to the artistry conveyed through diversity, that are privileged with the ability to see the world through many eyes. Conforming to society’s perception of beauty is merely an exercise in palatability. Therefore, appreciating my background, culture, and divergence from the socially accepted, I will continue to advocate for those who feel as though they do not belong. Why? Because, “Owning our story and loving ourselves through that process is the bravest thing that we’ll ever do”.

TIPS FOR PARENTS WITH BIRACIAL KIDS

My parents have always exposed me to both sides of my culture equally. My mother was raised in a Baptist Christian household and my father was raised as a devoted Muslim. I have been exposed to both religions growing up, enjoying the festivities belonging to both sides. My parents raised us to understand that we are indifferent to our cousins whom are either fully black or fully Bangladeshi/Pakistani. The key to growing up mixed for me has been to understand my differences and to embrace them. I think it is most important that parents expose their children to all aspects of their cultures, and try to maintain as much of all of their unique ethnic backgrounds. Close minded community members fear the “loss of culture”, but one thing I can assure is that I’ve never lost mine.

Thank you Sitara for this eye-opening, eloquently put, and engaging interview. Are you a parent with biracial/multiracial children? What do you think of Sitara’s interview/story? Feel free to share this post and comment below! Have a question for us? Write us at growingupgupta@gmail.com

script async src=”//pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/js/adsbygoogle.js”>

3 comments found