My Search For Identity After Being Abandoned By My Indian Family

My Search For Identity After Being Abandoned By My Indian Family

An Interview With Sharda Sekaran

A friend of mine sent me an article entitled, Black Mom + Indian Dad=Search For Identity. The article appeared in Ebony magazine some years ago by Sharda Sekaran, an esteemed writer, story-teller, and political activist. Her impassioned words cut like a knife. As she shared, “when people casually ask me how my Indian grandparents reacted to my father marrying a Black woman, I struggle to think of a more cheerful way to explain that they threatened suicide at even the insinuation of such a thing and, according to my mother, my father eventually caved to social pressure.’ I always try to quickly change the subject when Indian people quietly (sometimes not so quietly) judge me after I explain that I don’t speak my family’s language and have never visited India.”

Sharda’s pain and isolation left me emotionally unhinged. I looked down at my 5-year-old daughter, and my eyes swelled, and I hugged my husband tightly, and I ugly cried. Because I knew deep down inside that could have been us, it could have been our story. And no child should be forsaken because their mom or dad is deemed the wrong race, ethnicity, or color. At that moment, I knew I had to find a way to reach her. Within a week, we made contact with each other, and Sharda agreed to do this interview with me. An interview that I hope is not only telling but transparent and curative too.

Tell me a little bit about yourself (introduce yourself and your ethnic background, etc.)?

Sharda: I’m my mother’s only child. She’s African-American with origins in Valdosta, GA, where both of her parents were born. She grew up in Detroit, MI. My father was from India and grew up in Mumbai.

Where did you grow up?

Sharda: My father abandoned us when I was a baby. He left, and I never again saw the man whose mother’s name and whose first name I would carry through life. With few job opportunities in Detroit, my mom and I moved to New York City when I was five-years-old. I grew up in Queens, NY.

How did your parents meet?

Sharda: They were both studying at Michigan State University. My mother was an undergraduate student focusing on urban planning, and my father was an international graduate student from India working on a Ph.D. in chemistry. At the time, my mom had an interest in photography. She thought my father was striking and asked to take his photo. That’s how they met.

How did your grandparents react to your parents marriage?

Sharda: My father’s parents were in India this whole time. I know they threatened to commit suicide if, after coming to the US, he married a woman who wasn’t a high caste Indian of their choosing. Whether, they actually learned that my parents were married or that I existed is something I don’t know. I also don’t get the impression that they would have been too fond of the idea.

When did you realize you were biracial?

Sharda: My black family members and plenty of other people in our community tended to make a whole lot of comments about my hair. In particular, that it grew long, that I had “Indian” hair and all of that. It was one of the essential ways that I was constantly reminded of being mixed and other. I was never really around South Asians until I got to the sixth grade and started attending a diverse elementary school in Queens. I was always aware that my name was Indian, and that there were aspects of my physical appearance that people thought made me “Indian.” Other than that, I knew next to nothing about South Asian cultures and identity growing up.

What has been your personal experience with prejudice and discrimination?

Sharda: Unfortunately, I feel like I experience a complicated matrix of prejudice and discrimination coming from many different angles. My Indian family abandoned me. That rejection was my first introduction to prejudice and discrimination.

As a child, I was bullied by kids in my neighborhood who resented the attention I got for having long hair. They didn’t think I was black enough or hated me for being different. When I got to mixed schools in Queens, I would get harassment from white students. Who made a sport out of taunting Indian kids by putting on stupid Apu accents and making jokes about red dots and curry. Fighting off anti-Blackness in the US and all across the world is an on-going struggle.

Have you found the missing half of your ancestry and have you made peace with it?

Sharda: I still struggle with the Anti-Black biases that are all too prevalent in the South Asian community. It’s enraging and frustrating. Things have gotten a bit better. I meet a lot more mixed South Asian and Black families. There are still way too many bigots among South Asian grandparents, aunties, and uncles. But it’s nice to see more mixed kids (and not just the ones who are mixed with white) being accepted. That gives me more hope for my place in the community. Despite the racism part, I’ve long felt a compelling connection to the cultural aspects of my ancestry – the food, music, dance, art, celebrations, literature, philosophy, spiritual principles, and visual beauty of South Asian heritage speak to my soul.

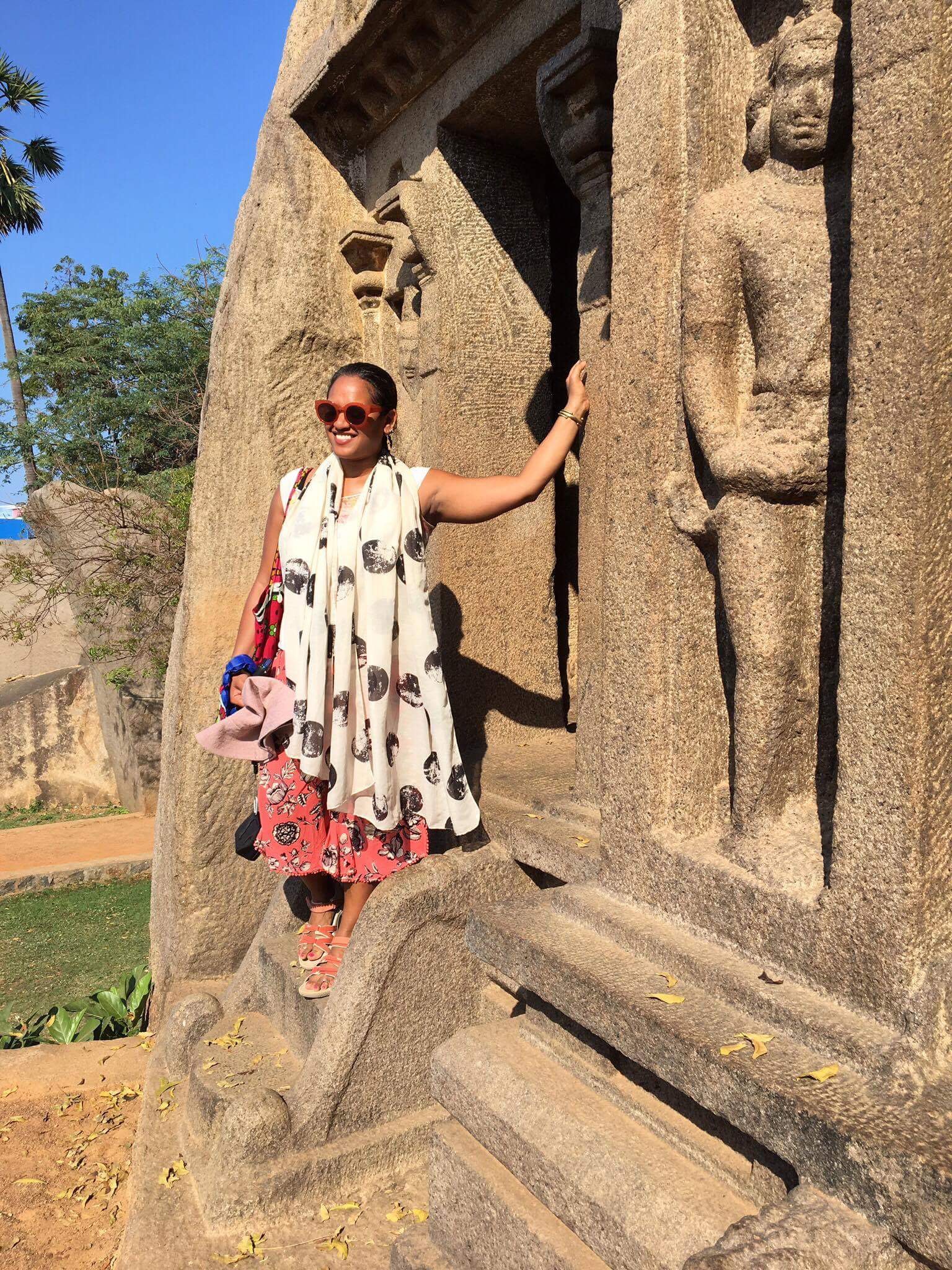

I read in the article that you wrote for Ebony that you visited Africa. Have you visited India? If so, what was your experience like in India?

Sharda: I visited India for the first time in 2017, at the age of 40. It took me a long time to get around to this trip. Honestly, for many years, I deliberately avoided India because it felt too emotionally loaded of a journey. I was afraid of feeling even more rejected. Much to my surprise, I loved being in India. I stayed in the south and spent the greater part of my time in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Of course, there were challenges and concerns. India is India. But overall, I felt incredibly at home, welcome, and warmed by the whole experience. The connection to something deep inside of my being that was long neglected felt genuinely profound. Also, it was revelatory to see dark-skinned South Indians going around looking about as black as black can be. I could recognize the anti-Blackness I experienced from Indians as part of deeply ingrained self-hatred, colonization, and caste discrimination. I went back to India this past February, and I plan to continue visiting South Asia in the future.

Where are you today with your identity? Do you celebrate your origins today? If so, how?

Sharda: I feel that it is my responsibility to myself and my ancestors to celebrate my origins. Embracing my Indian-ness is an act of resistance and self-actualization because ignorance and bigotry conspired to try to deny me of this part of my origins. Embracing my Blackness is an act of resistance and self-actualization because bias against black people is systemic and global. Choosing self-love is a powerful antidote.

When I got married last year, it wasn’t a traditional or formal ceremony, but I wore a sari for the first time in my life. It felt important to me. I try to honor my African and slave ancestors by engaging in human rights advocacy and fighting against racism. I have been involved in political activism in some form or another since I was a teenager.

What advice would you give other children that are divorced or abandoned from their cultural ties?

Sharda: Abandonment and rejection are a heavy burden to bear. I know that it has impacted me in profound ways. At times, I found myself in really lonely and dark places where I doubted my very right to exist. There is a lot of pain that I negotiate. It doesn’t go away. For those of us who carry family rejection due to racism and bigotry, it can feel like a whole culture and history has denied you. My advice is to keep in mind that the people who cause you pain are just scratches on the surface. Your connection to who you are and where you come from runs much deeper than them. The kids who attacked me when I was a child caused me trauma, but they are not the gatekeepers to my Blackness. I get to be as Black as I want to be. It is my birthright to bask in the beauty, talent, and magnificent legacy that are part of the Black experience.

Likewise, my Indian family does not get to decide if I am welcome in my own origins story. Nope, sorry, but I still get to be as South Asian as I want to be. With more than a billion people of Indian origin and tons of languages and cultural diversity all across the diaspora, inevitably, there must be a place for me. Mixed folks are blessed with a rich background that leaps beyond boundaries. We are gifted with a unique perspective on the world.

Sadly, many people are culturally insensitive to the unique struggles of biracial people. What do you wish others knew?

Sharda: I wish others knew that you can embrace all the parts of your origins without reducing the value of any of them. Identity is not zero-sum. If I am cooking Indian food or trying to learn Tamil, this doesn’t mean Team Black lost out today. If I am up in my Black family reunion doing the electric slide on the dance floor, it doesn’t mean I shut the door on being Desi. Some of us are more than one box. Some of us are even “all of the above.” Very few people have a 100% pure 23andme report. Perhaps learning to appreciate biracial people can teach everyone to become more enriched by their own complexities.

What did you think of this powerful and poignant interview with Sharda Sekaran?

Find her @ http://www.shardasekaran.com/

Are you following us at Growing up Gupta yet? Click the follow button now!

Also, follow us on Instagram, Pinterest, Facebook & Twitter.

Pin this article for later!

This blog post contains affiliate links which support the operation of this blog!

1 comment found